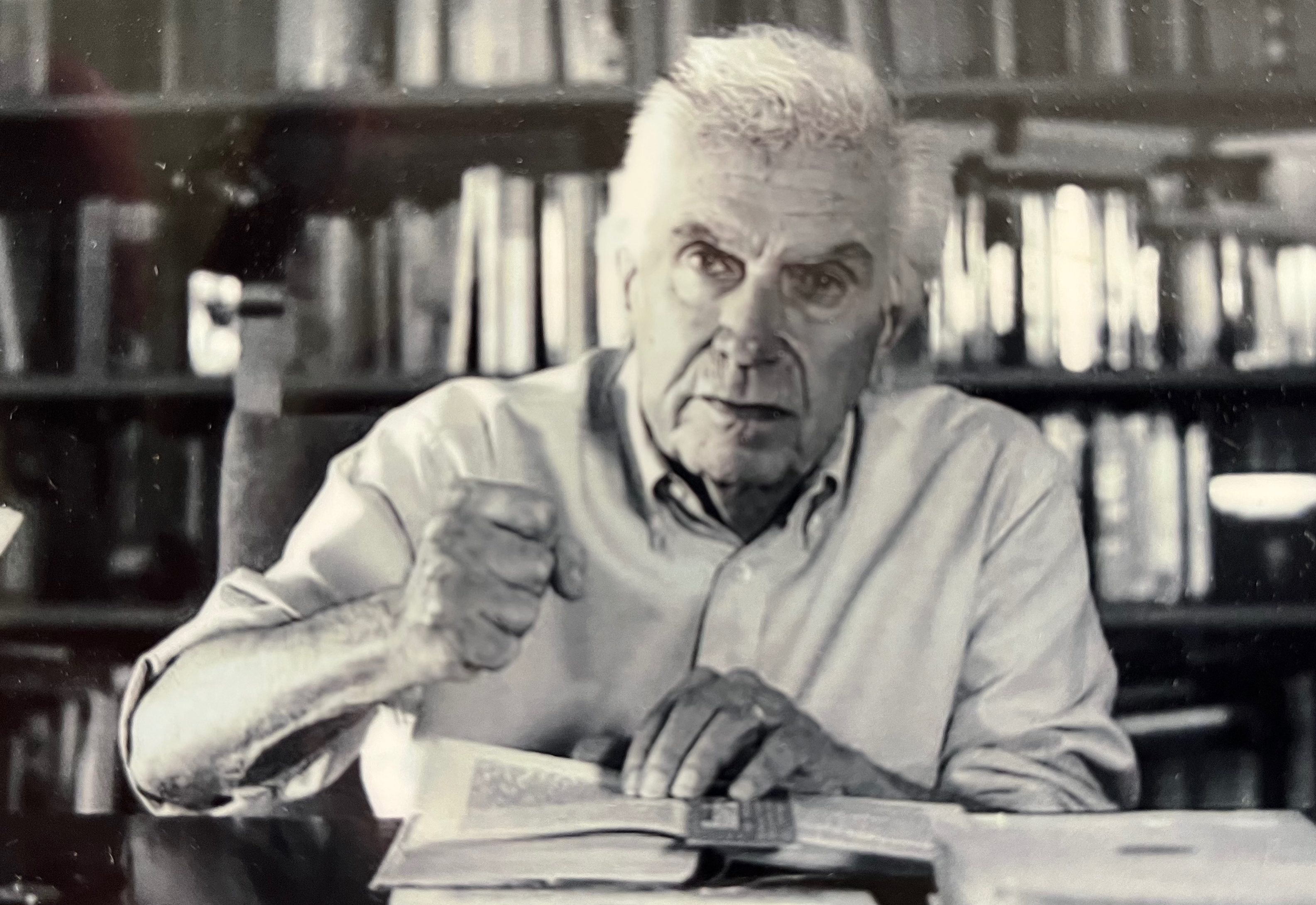

I met Mario Tronti for the last time in his office in the Senate, in the room adjoining the one where Galileo Galilei was tried for heresy over four-hundred years prior. Thankfully, Tronti had nothing of the Inquisitor about him. If there was something clerical about him, it was that of a quiet but charismatic friar – a Dominican to Toni Negri’s Franciscan one might quip – a member of an ascetic mendicant order, of few if always quiet and weighty, and sometimes fiery, words delivered in lapidary fashion. Having said that, he was not at all dour or intimidating. There was often a sense of amused knowingness, which I sense hid a certain shyness, certainly a reserve. He seemed entirely suited to the little monkish study, adorned with three lone Durer prints, where he wrote in the Umbrian town of Ferentillo. That was where his family originated, but he was born and grew up in the bustling working-class neighbourhood of Ostiense in Rome. He kept a flat a few doors down from where he was born where he spent his time when he had meetings or wanted to use the library of the Senate, where he sat between 1992 and 1994, and then between 2013 and 2018. It was said that when he took the bus to the Senate wearing the suit and tie without which he could not gain admittance to his office, his embarrassment at sitting in formal bourgeois attire among the popolo of which he felt so much a part meant that he covered himself in a heavy overcoat in all weathers. It was as if he feared losing, even for the duration of a bus trip, that contact with the side to which he had asserted partisanship from the start.

That last meeting took place in late May 2022, after he sent me a touching email in memory of my father, who had died in March. The email was written in what, on the page, appears to be a poem, and in his characteristic oracular style, which became more marked as he approached and then made his way into the ‘age of the patriarchs’ (in the expression he took from Carl Schmitt’s reply to Ernst Jünger’s well-wishes on the occasion of his 90th birthday).[i] Tronti and my father had known one another when both were members of the Central Committee of the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI) in the 1980s. This was the declining phase of the party’s fortunes, shortly before its public self-immolation at the start of the following decade, on 3 February 1991; only eleven months before the much more consequential dissolution of the Soviet Union on 26 December of that same year. The latter date marked, for Tronti, what he would soon call the twilight of politics, in his book of that name (Il tramonto della politica, 1998).[ii] Despite Tronti’s reservations regarding Eric Hobsbawm’s talk of a ‘short Twentieth century’, for Tronti, the century of politics could be thought of as bookended by the same historical moments demarcating Hobsbawm’s short century: 1917, when the great masses first came onto the scene of history, becoming its active participants, and 1991, when the dream of the alternative, the necessary utopian moment of ‘great politics’ – despite its corrupted form, which Tronti acknowledged – ceased to be. 1991 not 1989 was the crucial year. As he wrote in The Twilight of Politics: ‘1989 is not, will not be, an epochal historical date, despite the spectacle put in place by the pied pipers of the counterrevolution. Nothing begins in 1989, because nothing ended there. It took three years, from 1989 to 1991, to bureaucratically certify the death that had occurred many years before’.

With 1991, we see Politics defeated by History, for politics is the tool of the weak against the powerful whose power is not won but bestowed up them by the force of historical, which is to say technical-economic, necessity. The powerful have no need of a politics when the subaltern classes – or class, more specifically the industrial working class – loses its capacity to politically organise itself against History. For power is either History’s bequest to the ruling class, or, very occasionally, what the working class wins for itself through the ‘weapon of organisation’ (to take the felicitous title of Andrew Anastasi’s collection of Tronti’s writings from the 1960s), via the skilful application of the art of politics. (As he was wont to say in his later years, itwas necessary that Capital and the bourgeoisie come once again to fear the working class,). From 1991 to his death, Tronti – the erstwhile ‘father of Operaismo’ (or Workerism) – assumed what he felt was his responsibility: to wrest the memory of twentieth-century communism and communists from the ‘miserable age of Restoration,’ or, as Walter Benjamin put in Thesis VI of ‘On the Concept of History,’ ‘from the conformism that is working to overpower it … convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he is victorious’.[iii] One must be careful not to read into Tronti’s account a wistful paean to the world of yesteryear à la Stefan Zweig. His is rather an angry, Nietzschean denunciation of the self-satisfied smug onanism of the ‘most contemptible person’, the Last Man who is incapable of even generating the semblance of an ideal, of a desire that cannot be found on the shelves of a shopping mall. As we read in Thus Spake Zarathustra: ‘Then the earth has become small, and on it hops the last human being, who makes everything small. His kind is ineradicable, like the flea beetle; the last human being lives longest’. Not Trieb but Instinkt is what governs the contemporary Anthropos of the Last Man after the end of politics. That Anthropos swims now in what the fifteenth-century prophetic friar Girolamo Savonarola called the ‘filth and iniquities of the wretched world … like a beast among swine’.

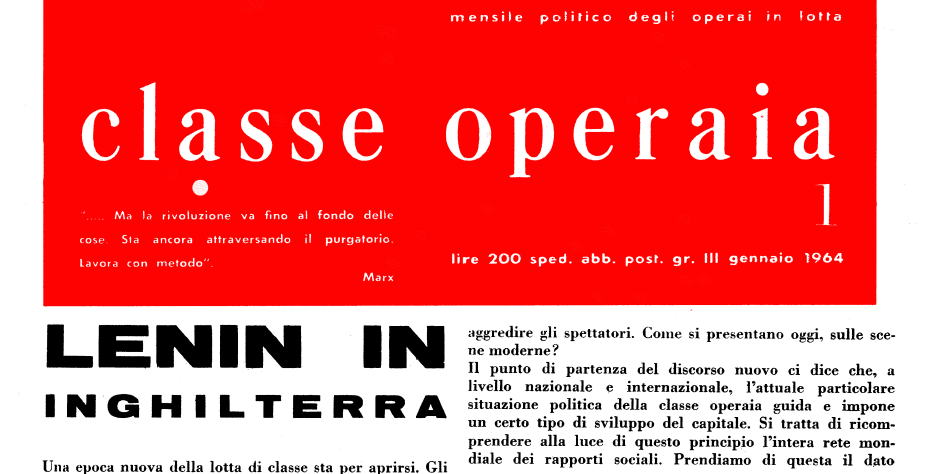

I cannot hope to provide a full account of Tronti’s development here. Instead, I will highlight certain moments without which one loses the breadth of this ‘politician leant to the world of philosophy’, remaining tethered instead to the brief and best-known phase of his political thought to which I shall turn first. Operaismo is the tradition with which Tronti continues to be associated, even when he declared that, as far as he was concerned, Operaismo began circa 1960 with the journal Quaderni Rossi (under the leadership of Raniero Panzieri), and came to an end in 1967 with the final issue of the journal classe operaia (founded in 1964 by Romano Alquati, Rita di Leo, Negri and Tronti, amongst others, after a break with Panzieri).[iv] While he never reneged on Operaismo, his periodisation served to situate this body of thought and practice at the close of the period of what he would call ‘great politics’ (circa 1917 to 1968, after which, he suggests, politics continued until 1991 in a minor register). In short, Operaismo took flight at dusk, when its moment had passed, like all great philosophies. That Operaismo aimed to be so immediately tied to practice, to contemporary action, is what so tightly circumscribed its historical limits (practical and theoretical) to a time that was fast running out. This was, he argued, in part due the shifts subsequent to 1968: away from the immediate process of production and from the industrial worker as collective subjective of the movement, moving from the workers’ movement to many movements, from anti-capitalism to anti-authoritarianism, from revolution to rights – and to identity politics, one might add.

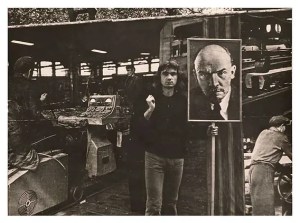

Perhaps the core tenet of Operaismo was contained in the famous editorial, ‘Lenin in England’, from January 1964: ‘at the level of socially developed capital, capitalist development is subordinate to working-class struggles; not only does it come after them, but it must make the political mechanism of capitalist development correspond to them’. This claim, Tronti later realised, was true not of capitalism per se, but only of a particular historical moment of the workers’ movement, and so only a specific period of capitalist development, the one that ceases with the end of the Fordist-Keynesian compromise. ‘The working class of the great industrial concentrations bore class conflict to the highest levels of conflict. Not the disappearance of industry, but the disappearance of large-scale industry was the critical discriminatory passage. The blunt fact was the mass worker. There, for the first time, dependency upon work freed itself from social subalternity. There, the potentially political working class was the emancipatory class’.[v] The ‘mass worker’ was not, for him, a sociological category, it was a political or organisational one – for the class only exists as a class, i.e., as something more than variable capital, when it is organised.

To put the issue of organisation in its most concise form, it concerned the relation of the working class to the party (as its form of organisation) on one side; and, on the other, which is to say for capital, it concerned the relation of the capitalist class to its state (as its form of organisation). If the task of capital and its state is to reduce the worker to a fragment of capital (i.e. to variable capital, turning labour-power into a commodity via the wage system and then subordinating it through the system of machinery and managerial organisation), it is the task of the worker to refuse such a reduction (the ‘refusal of work’), to reject labour’s organisation by capital and to organise the working class as a class against capital and its state. Hence the famous phrase describing the Janus-faced character of the working class, in the central essay of Operai e capitale, as ‘within and against capital’: within, in that capital tries to increasingly reduce the worker to being a fraction of capital; against, the workers as a class, as an organised subject, forms itself in opposition to capital.

Whereas the individual capitalist confronts the individual worker on the labour market in buying the commodity labour-power, he can only avail himself of that commodity’s use-value (to produce surplus value) by organising the worker in the process of production. In so doing, Tronti – in his rereading of Marx – shows how the worker never exists as an individual (other than on the market), but since the worker’s labour-power is only bought in order to be organised in the process of production as cooperative, collective labour, workers are necessarily organised as a class. So, the working class does not precede capitalism, it precedes the capitalist class. It is only once the working class organises itself politically, which is to say as a class in the face of exploitation in the labour process, that the capitalist class too can take shape, without which capitalism could not survive. For individual capitalist competition can lead the system to ruination and only its political organisation as a class – as a collective capitalist or bourgeoisie – can constrain individual capitalists to save capitalism from itself.[vi] For this reason, the ‘working class is the secret of capitalism’, as Tronti writes in an editorial from 1962 from Quaderni Rossi included in Operai e capitale.

This critical issue, the so-called ‘problem of organisation’, which is to say, ‘the problem of the party’ that existed in one form or another from the foundation of the journal classe operaia, would eventually bring Operaismo to and end (or at least did for Tronti).[vii] At this point, members of the disbanded editorial boards took a variety of directions. Many remained in the extra-parliamentary grouping and would eventually found others, such as Potere Operaio and then Autonomia Operaia. Many of these figures would later be imprisoned or flee into exile after the crackdown, often on trumped-up charges, following the killing of Italian Prime Minister, Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades in 1978. Tronti, and a few others (notably the philosopher Massimo Cacciari and the literary and cultural critic Alberto Asor Rosa) would gradually make their way into (or back into) the PCI.

In 1979, Tronti, writing in the daily Il Messaggero, defended his erstwhile collaborator during the years of Operaismo, Antonio Negri, from the series of increasingly hysterical accusations that had led to his imprisonment. At the same time, Tronti demarcated the thinking of Operaismo from that of Autonomia operaia, of which Negri was a leading light.[viii]For Tronti, the core distinction turned upon the question of ‘worker centrality’: always face-to-face with the bosses, one standpoint against another, class against class in a binary logic of friend/enemy. Tronti accuses Negri and others of leaving by the wayside this core tenet of Operaismo. The ‘Autonomists’ advanced the notion of a proliferation of new subjective forces, floating free from the immediate process of production, postulating not class confronting class directly at the core of industrial capital, but instead the spontaneity of proliferating antagonisms in conditions of marginality, generalised unemployment, and fragmentation set against a state machine reduced to its apparatus of repression. While Tronti was happy to accept that such a proliferation of social subjects was real, he refused Autonomia’s decision to turn these figures (the ‘social worker’ in the 1970s-‘80s would be multiplied in later decades into ‘immaterial workers’, ‘cognitive workers’, the ‘precariat’, the ‘multitude’…) into moments of political centrality, no longer linked – and often opposed – both to the industrial working class and certainly to the institutions of the workers’ movement.[ix] For Tronti, without worker centrality and the accompanying ‘point of view’ or ‘partisan synthesis’ that marked it, one had left Operaismo behind.[x] This was a point at once political and epistemological, and without it Operaismo ceased to operate theoretically or practically. For within capitalism, as declared in Workers and Capital, ‘the whole can only be comprehended by the part. Knowledge is tied to struggle. Only those who truly hate, truly understand. This is why the working class can know and possess everything of capital: because it is even the enemy of itself as capital. Whereas the capitalists find an insurmountable limit to the knowledge of their own society, in the very fact of needing to defend and conserve it’. By contrast, the multiplication of subjects by the Autonomists followed a sociological, empirical definition of ‘class’ that did little more than ride the wave of history, of immanence. By foregrounding their marginality, such subjects no longer thought of themselves as within but merely against, and capital collapses into the Moloch-like State machinery’s repressive apparatus, thus encouraging a militaristic conception of struggle and losing any partisan epistemological advantage over its enemy. This – Tronti implied – was a form of tailism in the guise of voluntarism, a ‘political romanticism’[xi] that abandoned the cognitive tools necessary for a revolutionary politics.

It is perhaps here that we begin to see the properly philosophical element that defines Tronti’sthought: bringing together conflict and transcendence,[xii] marking the specificity of his anti- (mainstream, or Stalinist) Hegelianism. For him, conflict is not a moment of development, a marker of immanence’s progressive mobility and flexibility, but produces dichotomies, contradictions, oppositions. Politics is a blade that slices and pierces through being, rupturing History’s continuity, replacing unity with opposition, multiplicity with dichotomy, producing a caesura within the immanence of the technical-economic order and establishing contradictions, subjective standpoints at war.[xiii]

I recall a seminar in 2004 at the Fondazione Basso in Rome, where Giorgio Agamben, Roberto Esposito, Negri and Tronti were invited to speak on the issue of biopolitics. Tronti was the last to speak, and started by saying that he did not know why he had been invited, for the immanence embedded in the concept of biopolitics jarred fundamentally with his own thinking. In conclusion, Tronti made two fists that he ground against one another, slowly but forcefully turning knuckles against knuckles: ‘For me it is all about class against class, at war’. It is important to note that this was no mere Marxist class reductionism, for without the ‘weapon of organisation’, class does not exist. If there is a reductionism in said that remark, it is an inflationary one – of an almost metaphysical order. For what is sometimes ignored in Tronti’s radical rereading of Marx – especially if contrasted to that which was dominant within the Italian ‘national-popular’ and historicist discourse of the PCI – is its embedding in a Nietzschean and Weberian re-reading of both Marx and Lenin. Against the ‘Hegelian’ tryptic (thesis-antithesis-synthesis), which ended in a pacific resolution of conflict in the whole, he proposed a ‘dialectic’ of the two in irresolvable conflict.[xiv]

Here, politics implicates a subject that rends the fabric of reality, a radical Nietzschean perspectivism, a Weberian world of infinite, chaotic multiplicity where ‘points of view’ cleave chaos and disassemble the mechanisms of immanence, of smooth exchange; and where order stems from the techno-economic unfolding of History or through Leninist decisionism. This is the same decisionism that would fascinate Carl Schmitt (who would become another reference point for Tronti from the 1970s), one that forms the subjects, the ‘intensity’ of whose conflict marks out the political as that which ruptures the dialectical progression of History in what the young Gramsci famously called a ‘revolution against Capital’.

As Schmitt observed in Political Theology II: ‘A conflict is always a struggle between organisations and institutions in the sense of concrete orders’ constructed from conflicting subjects. ‘Substances [collective subjects, M.M.] must first of all have found their form;’ Schmitt continues,‘they must have been brought into a formation before they can actually encounter each other as contesting subjects in a conflict, that is, as parties belligérantes.’ So, the question of subjective organisation is a condition of conflict, but conflict necessarily accompanies the formation of contending subjects. This account of the irreducibility of conflict would accompany Tronti through to the end but would instantiate itself differently, assuming almost the status of a political ontology. As Tronti wrote in 2015 (Il nano e il manichino), ‘Political theology could only enter the literature [in 1922, in Schmitt’s Political Theology], which is to say, become conscious, or self-conscious, in the Great Twentieth Century, in the age of European and world civil wars. When History falls to a lower level, when the antagonistic alternatives are extinguished, political theology no longer has a raison d’être. Then it is not a theological impossibility, but a political impracticability of political theology. It is what happens today’, the time of the last man and the ‘dictatorship of majority opinion’, dominated by ‘the chorus of mass intellectual common sense’.

I think it is worth adding that Tronti’s relationship to Hegel has yet to be adequately reflected on, with many too easily seeing Hegel as the ‘enemy’ or at least the foil against which Tronti’s Nietzscheanism erected itself. It is in fact rare to find explicit critiques of Hegel in Tronti. It is far more typical for him to affirm specific aspects of Hegel’s thinking, leaving to one side other dimensions (such as the overall project of a Science of Logic), and focusing instead on the advance Hegel represents in thinking politics, or the relation of ethics to politics, or in the construction of the dynamics of the subject. In a May 2017 interview with Podemos founder and former Spanish deputy PM Pablo Iglesias on his TV series, Otra Vuelta de Tuerka, , Tronti is asked a series of concluding questions, one of which is who he considers to be a maestro (teacher, guide, mentor). After a brief series of remarks, in which he notes his distaste for thinking in terms of master and pupil, he says: ‘From the theoretical point of view: the Hegel-Marx relation; together…. I always think of them together. For without Hegel there would have been no Marx. And Hegel would not have been what he has been for me, which is to say a lot, without Marx’s critique.’[xv]

The choice Tronti made for the Party – for the PCI, which he had never left but just stepped back from – in 1966-7, was driven by an acknowledgment of the expansion of the growing tide of workers’ struggles, within but mainly outside the leadership of the institutions of the workers’ movement. It was the very size of such a tide that meant it was beyond the coordinating capacities of what he called the proliferating ‘groupuscules’ through which the Italian ‘New Left’ had attempted to organise the tide. What was needed, he now declared, was organisational capacity on a vaster scale: from varieties of workplace struggle to the trade unions to a party seeking to govern the state and envisaging direct and indirect involvement in economic planning. This exigency led to a proposal that soon turned out to be no less tenuous or evanescent than that of those who argued for a spontaneous uprising of a multiplicity of revolutionary subjects (Potere operaio, Autonomia operaia, Negri, and so forth): the call for the creation of a cadre of militants in the factory who could be transferred into the Party, to change it from within.

In 1965 a debate had begun in classe operaia and beyond, on the need for the ‘party [to be] in the factory’,[xvi]which is to say, on the need to re-establish a link between the PCI and the working class, a link broken – it was argued – by the PCI’s historicism grounded in a national-popular strategy of broad-based class alliance. Tronti now argued that the Party could only enter the factory if the factory had already entered the Party. Hence the call for a cadre to be built within the factory and then to find a way into the Party. Such an operation would then permit the ‘autonomy of politics’, which is to say, a two-pronged strategy where the Party would be free to make tactical decisions independent but in the service of expanding struggles within the factory. At the same time, factory struggles could advance demands of their own without having to consider the tactical manoeuvring of the Party in its struggle to take command of the state, which would include a politics of class alliances not to be envisioned in the factory struggles themselves.[xvii]

The task of the PCI in this context, Tronti would argue, was to wedge itself between capital, the bourgeoisie, and its state and so become the political fulcrum from which to manage the economic, social, and political crisis within which 1970s Italy was caught. It was in these years that Tronti would begin extensive study of the entire history of the bourgeois state in order to learn how it might be turned into a tool against its class, resulting in a definition of the Christian Democratic party (DC) as the ‘party of pure mediation’. In the end, the DC found ways to manage consent as a means to attenuate, absorb and reroute social conflict by reducing them to individual interests. To be more precise, in the concrete situation of 1970s Italy, the DC had over a thirty year period become identified with the institutions of Italian democracy, thereby posing a limit to the possibility of democracy to truly represent social conflict. Conflict was thus ideologically transformed into consent to the institutions but in reality, in the social, conflict existed unable to be politically, institutionally mediated, to find political expression. The result was a crisis of the State and of democracy itself – evident in the proliferation of socio-political extremes. In later years, Tronti would argue that it ‘was not capitalism that defeated the workers’ movement. The workers’ movement was defeated by democracy’. ‘This democracy’, he declared in The Twilight of Politics, ‘is the self-government of the last men. The extinguishing of politics’, where atomisation and reduction of the demand for power to the demand for interests and rights undermines the political power of the large masses that alone can effect political change.[xviii]

The failure of this call for the ‘autonomy of politics’ is multifaceted. Tronti often blamed the fact that neither side, the PCI nor the extra-parliamentary left understood the call. Tronti also accused the PCI of always, in the words of Jamila Mascat, ‘lagging systematically behind the demands posed at the social level (the factory struggles but also that of the youth movements), and thus always develops inadequate responses’.[xix] But arguably there were objective as well as subjective conditions that were insufficiently grasped, not least of which was that the PCI’s scope of manoeuvre was even more limited than the ‘limited democracy’ that characterised Italy as a whole.[xx] A first draft of this systemic constraint was provided by the division of spheres of influence at Yalta, but by the 1960s-‘70s this was not only a geopolitical question, but increasingly one of (un-)governability.[xxi]

The ‘strategy of tension’ that had been developed in response to the fear of the expansion of social conflict and the increasing vote share of the PCI, put the Party on the back foot. It became increasingly blamed for the widespread violence (which in most cases was later to be found to be orchestrated by branches of the ‘deep’ state) and meant that only by extremely careful, skilful manoeuvring, a particularly refined ‘art of politics’ might possibly have been able to maintain the parliamentary course taken by the PCI. It too might well have been too little given the range of forces arraigned against such a strategy. Was there another course between the Historic Compromise and the governments of national unity against (Red or Black) terrorism on the one side, and the revolutionary tactics of ‘mass violence’ of elements of the extra-parliamentary Left, on the other? To be sure, the PCI’s attempt to isolate the Left – and its often-despicable compromise with the police and judicial repression of social conflict – served to render the Party, in the view of many (but also objectively), a servant – willing for the PCI-Right, unwilling for the PCI-Left – of reaction, and to divorce it from many of the social movements and even large swathes of the workers’ movement for a critical period of the 1970s. Whereas the actions of Autonomia operaia, and others, could arguably be said to have played into the hands of the reactionary forces. While certainly Tronti stood against such a strategy of isolation of the movements (if not of its armed factions), alongside some others from the traditional PCI-Left, the extent to which structural conditions rendered a middle course impossible remains an unanswered question, one that arguably inscribes the hopes of the revolutionary subaltern struggles of the latter stages of the Cold War into a broader history of the tragic condition of emancipatory politics.

The questions of breaks or continuity – namely whether a course of intellectual development is to be understood as a sequence of breaks (or ‘betrayals’) or a continuum composed of different elements rising up or receding, as when one glances over a canvas allowing images to come in and out of focus while all are nevertheless present – can be useful but is often without a final answer. Even the politico-theological move that Tronti makes in the 1980s, which at first sight would seem to mark just such a break, can be seen to be sutured to his earlier reflections, culminating in The Twilight of Politics and initiating a final period that Matteo Cavalleri, Michele Filippini and Jamila Mascat summarise with the title of ‘thinking the twentieth century’.[xxii] In the course of this politico-theoretical obituary, I have tried to touch briefly on each of these phases, though not in rigorous chronological order, choosing to see echoes and resonances rather than clean breaks. The breaks, if there are such things, are marked rather by scale and scope, rather than conceptual shifts. I would claim that Tronti’s thought is best understood as a deepening of conceptual categories that traverse his thinking, which at each juncture is enriched as his scope widens or burrows down.

So, one might speak of a phase of critique of Marxist orthodoxy (principally that of Italian communism and Stalinism) in his engagement with the critique of the political economy of industrial capitalism, in particular in its Fordist phase, which proceeds by thinking politics-as-organization as the missing link of critique. Then, a phase of the critique of the political itself, understood as a bourgeois form that the workers’ movement needed to learn to manoeuvre within to achieve power, and which required concerted research into the emergence of the bourgeois state, widening the scope far beyond the twentieth century: from Cromwell to Hegel, from Roosevelt to Christian Democracy. With the receding of the movements of contestation and, more importantly, the weakening of the workers’ movement in the 1980s onwards, Tronti’s viewpoint becomes increasingly epochal as it turns to political theology (this is what Cavalleri, Filippini, and Mascat call the period of ‘realism and transcendence’). And there is a final phase marked by the rethinking of the history of the workers’ movement at its highest moment, which Tronti reads as the culmination – and fading away – of modern politics itself. Concepts reappear, sometimes with new nomenclatures, throughout this long trajectory that seek always to salvage politics – organised conflict – from the processes of what Schmitt termed ‘neutralization and depoliticisation’.

As I mentioned at the beginning, when asked to write this obituary, now over a year after his death and as I try to work through the loss, my mind returned to the generous email Tronti sent me on the occasion of my father’s death. One particular line returned to me, that I quote, not without some hesitation: ‘Un esempio per tutti il compagno Francesco Mandarini, da operaio a militante a dirigente a governante. Gloria a lui!’ [Comrade Francesco Mandarini was an example to all, from [industrial] worker to militant to leader to governor. Glory be to him!]. What struck me, pride aside, was the path that Tronti traced here. In this short phrase, he provides the skeleton trajectory of the political subject that I have tried to outline: that is, of the political subject at the high point of modern politics, that of the mass worker that Tronti theorised as the bearer of a politics, without which politics would have been reduced to the mere administration of things as disposed by the techno-economic forces of History. From the struggle in the factory, in the immediate process of production, to the militant organisation of that struggle. Then political leadership through careful, tactical manoeuvring within the Party necessary to guard against the isolation of struggle behind the factory gates. And, finally, to the control of the tools of the state institutions. ‘Glory’, finally, operates as a concept marking the necessary moment of transcendence, the concrete utopian moment that refuses the reduction of change to innovation, refuses the Gattopardismo where ‘tutto devo cambiare perché tutto resti come prima’ [‘everything must change so that everything can remain the same’],[xxiii]where one forgets that every innovation is a failed revolution, and where political realism would otherwise sink into opportunism. Glory, transcendence, is to be understood as an utterly material moment of politics, albeit sacralised, without which politics ceases, change is nothing but marketing, and the subject is hollow.

As Tronti writes at the end of his last, as yet unpublished final essay, taking for its title a famous phrase of Hegel’s on the nature of Philosophy, ‘[one’s] own time comprehended in thoughts’:

Approaching the way out of the desert, putting an end to exile, and taking up the path to the promised land is the task taken up by the modern proletariat, inheritors of all the insubordinations of the subaltern classes. A task that is to be rewritten in the most unfavourable conditions we have ever faced…. There is a theoretical miracle that only a sacred secularisation can see and so put into practice. It is anything but abstract, it is very concrete, a revolutionary politics that puts in play a “creative tension” between the City and the Temple, between the Temporal [il Secolo] and the Sacred. It is not difficult to translate these metaphors into slogans for the organisation of struggle. It has already been done after all. Written, engraved forever in the memory of the workers’ movement are the past insurgencies that, albeit defeated, sought to storm heaven. From this memory of the past one must set out anew, to seek again to win a new tomorrow [avvenire].[xxiv]

Hence, for Tronti, the era of modern politics ends with the defeat of the workers’ movement.[xxv] But this never implies resignation and the accompanying wistfulness for bygone years, though I won’t pretend that the shadow of nostalgia is entirely absent, whatever Tronti’s protestations. What predominates, however, is a disenchanted, ruthless criticism of all that exists grounded in a subjective standpoint of conflict from within the domination of the forces of History. ‘I must understand’ was the later Tronti’s categorical imperative. Not only must one understand that a great history can come to an end, that of the workers’ movement, that of modern politics, and ‘how it can end wretchedly’ (Dello spirito libero, 2015). But more than this. The epistemological standpoint of conflict had to be reawakened and reasserted. At the heart of Operai e capitale was the working class as the subject within and against capital, a fragment of capital in conflict with it. Salvaging conflict is an epistemological and practical moment, a categorical imperative cutting through bien pensant‘common sense’ by means of the patient, guarded, suspicious labour of extrication of the subject as conflict, resistant to pacification in the untroubled complacency of the Last Man.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my thanks to Sarah Kelleher, Elena Baglioni, Tariq Goddard, Demet Dinler and Alberto Toscano for commenting on earlier drafts of this obituary. Many thanks also to Brenna Bhandar for first proposing the idea.

An abbreviated version of this obituary was published by Radical Philosophy, in December 2024: https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rp217_mandarini_tronti.pdf

[i] He had used it in an address, in parliament on 31 March 2005, for the celebration of Pietro Ingrao’s 90th birthday. Ingrao was a partisan in the Resistance, parliamentarian, and leader of the PCI Left since the 1960s.

[ii] The English translation, The Twilight of Politics (Seagull Books 2024).

[iii] As he was to write almost two decades later: ‘the past, once interpreted, subverts the present more than any imaginable future’ (Dello spirito libero, 2015).

[iv] The so-called ‘bible of Operaismo’, Operai e capitale (1966, expanded 1971 and again in 2008), contains many – but not all – of Tronti’s principal editorials from the two journals, as well as essays written specifically for each edition. It was finally translated into English as Workers and Capital in 2018. I have critically discussed the shortcomings of that translation in a review published in International Review of Social History, Vol 65, Issue 3 (2020): 547-550.

[v] Interview with Andrea Cerutti and Giulia Dettori, in La rivoluzione in esilio. Scritti su Mario Tronti, 2021.

[vi] This is very evident in Keynesianism, but we have seen how capitalists can operate as a class in times of crisis in the various bailouts we have witnessed over recent decades. This was already clear from Marx’s chapter on ‘The Working Day’ in volume 1 of Capital. There, Marx notes how state regulation emerges precisely as a means to curtail (or at least to alleviate) the hyper-exploitation of the workers in individual factories and has the further consequence of forcing capitalists to innovate in the system of machinery since they can no longer exploit labour by extending the working day. In that sense, every innovation is a failed revolution.

[vii] Tronti later claimed that, for him, the party was always (if tacitly) the PCI. Tacitly, because many members of Quaderni Rossi and of classe operaia came from the Partito Socialista Italiano (most notably, Negri and Panzieri), and elsewhere. It was when Tronti increasingly felt that the turn towards the PCI was increasingly politically urgent, and resisted by most of his fellow editors, that Tronti decided to close classe operaia in the face of widespread opposition.

[viii] Tronti’s demarcation of Operaismo proper from Autonomia shows the common collapsing of Operaismo into ‘Autonomism’, common in many Anglophone accounts, is both a theoretical of political choice that stands in profound contrast to Tronti’s own understanding of Operaismo. For Tronti this is a post-Workerism whose relation to Operaismo might be said to parallel post-Marxism’s relation to the Marxist tradition – not an internal critique, but a criticism that leads out of Marxism. For Tronti, Operaismo was always a strand of the workers’ movement itself and of its dominant theoretical standpoint, Marxism.

[ix] In my last meeting he said: ‘I think that those from Autonomia were more anti-communist than anti-capitalist’ (26th of May 2022). By which he meant, anti-PCI and the institutions of the workers’ movement more broadly.

[x] This partisan standpoint would remain with him to the very end, as is attested to even in what must be his final interview with L’Unità, the daily founded by Gramsci, from the 19th May 2023. The title of the article was: ‘Minimal Programme: To Recover Partisan Memory’ (‘Programma minimo: recuperare la memoria di parte’).

[xi] The accusation of ‘political romanticism’ of those who understood capital in terms of the State Moloch savaging human rights, is one that Tronti levelled in his lecture, ‘Lo Stato del capitalismo organizzato’. This was delivered at a two-day conference on the State and capitalism in the 1930s at the Gramsci Institute in Rome in November 1979.

[xii] Although the concept of transcendence only emerges in the 1980s.

[xiii] One can trace a direct line from the theory of the ‘point of view’ of Operai e capitale – itself echoing if not overlapping with the early Lukács’s reflections on the standpoint of the proletariat – to the repeated call to ‘partisanship’ of the later years: ‘One needs a point of view from which to look at the world and life. One needs a part of the world and life to which to ascribe one’s own thought…. The history of the workers’ movement has left us a bequest, you must go and seek your side [parte] with patient intelligence, with passion, thinkingly, tearing it almost day-by-day from the narrative that has buried it; piercing the veil of dominant ideas that have left it for dead, and then allowing it to be glimpsed from afar, with vision, allowing it to be touched close by, with realism, ever mindful of being and operating behind the bars of an iron cage’ (Tronti, Per la critica del presente, 2013).

[xiv] I put ‘Hegelian’ in scare quotes for it seems to me that Tronti took aim here not only at Gramsci’s historicism but also at the Soviet philosophy of Diamat. In critical comments on the dialectic, he was, for the most part, much less engaged in a concerted philosophical confrontation with Hegel himself. Arguably, one might claim that this is true in much of French anti-Hegelianism as well, from Louis Althusser to Gilles Deleuze, where it was Diamat and the PCF that were the principal objects of critique. It might be useful to note that Tronti’s only real, substantive text on Hegel (who actually appears throughout Tronti’s writings) – Hegel politico (1975) – was composed in the period of his call for the ‘autonomy of the political’, for which Hegel was, to his mind, a precursor. This was a Hegel that proceeded from the subject, a subjectivity ‘replete with political realism’, i.e., a step towards a ‘political class dimension’ that breaks the purported but absent ‘autonomy of the economic’(as he declared in a lecture on 5 April 1975).

[xv] The interview is available on YouTube, in Italian and Spanish: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzKymyIsj50&list=PLU8WjOORJXltNmKcUkant0ljJLTa1On03&index=20 – accessed 12the October 2024.

[xvi] For a very useful discussion, in English, see Andrew Anastasi’s excellent collection – and very useful introduction – to The Weapon of Organization: Mario Tronti’s Political Revolution in Marxism.

[xvii] The ‘infamous’ lecture, ‘L’autonomia del politico’, took place in 1972 but was not published until five years later. (An English translation is available online at Viewpoint Magazine with the title ‘The Autonomy of the Political’.) It was infamous for a number of reasons. The most important of which, I would argue, is that it never made explicit that the struggles in the factory should be autonomous from the Party. And so, it was read by many, particularly those from Potere operaio and, later, Autonomia operaia organizzata – who felt they were remaining true to Operaismo’s primacy of the antagonistic subject – as granting the PCI carte blanche, permitting it to act opportunistically, without an eye to the struggles in the factory. Hence, it was considered as a betrayal of the tenets of Operaismo’s class against class standpoint, by Tronti’s erstwhile and now-‘Autonomist’ collaborators, and was greeted with stony silence by the PCI intellectuals and institutional hierarchy, which was the intended audience. (It is likely that Tronti did not highlight the autonomy of the factory struggles, simply because his audience was the party establishment.) Andrew Anastasi and I have tried to answer the accusation of betrayal in ‘A Betrayal Retrieved: Mario Tronti’s Critique of the Political’, in Viewpoint Magazine.

[xviii] The critique of democracy would become a rich vein of research tapped by Tronti over the subsequent decades.

[xix] Thanks to Jamila Mascat for allowing me to read a draft of her insightful forthcoming paper, ‘Mario Tronti e il partito come problema: Fenomenologia del PCI e metafisica del politico’.

[xx] These ‘limits’ were posed by the unwritten but well-known block on the PCI ever assuming democratic command of the state. This was imposed in a number of ways by the USA and its allies: enforced through the US’s direct interference in Italian domestic politics (the State Department website shows the near daily communications with ministers in the Italian government throughout the post-war period); the intimate relationship between the Italian and US-NATO security apparatuses; the various ‘stay behind’ organisations the full extent and reach of which were not entirely uncovered until the parliamentary commissions of the 1990s; and the established relationship between organised crime, the security services, and elements of the Vatican.

[xxi] Consider, for instance, The Trilateral Commission’s Report, The Crisis of Democracy: On the Governability of Democracies (1975). See also Grégoire Chamayou’s The Ungovernable Society: A Genealogy of Authoritarian Liberalism.

[xxii] A translation of Il demone della politica is forthcoming.

[xxiii] Literally, ‘leopordism’, referring to the famous phrase uttered by Tancredi Falconeri in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard.

[xxiv] This long essay, which is shortly to be published in Italian, was one Tronti had been working on, on and off, for some years and was still working on shortly before his death. It is unclear whether this would have been the final version.

[xxv] That the best one can hope for from what goes by the name of ‘politics’ today, is to act as katechon, a withholding power ‘of the new modernity that kills the ancient greatness of the modern’ (The Twilight of Politics).